Housing Insights: Housing Poised to Become Strong Driver of Inflation

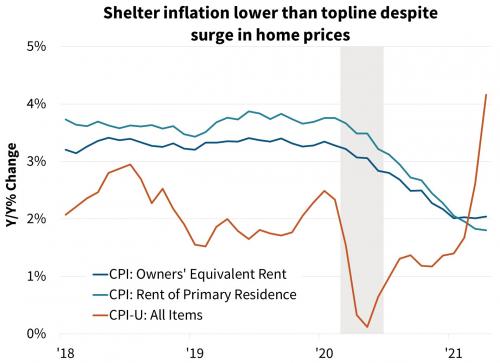

- The Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator (PCE) jumped to their highest annual rates since 2008 in April and are likely to accelerate further in the near term. However, due to how shelter costs are measured, the housing components of the indices decelerated considerably over the past year, despite strong home price appreciation. This has kept topline inflation from being even higher.

- Lagged effects from the past year's house price appreciation and more recent rent recovery could begin to flow into inflation measures as soon as the May readings. House price gains to date suggest an eventual acceleration in shelter inflation from the current rate of 2.0 percent annualized to about 4.5 percent. If house price growth continues at the current pace, shelter inflation would likely move even higher.

- Timing lags suggest increasing shelter inflation will last through at least 2022, meaning "transitory" increases to the rate of overall inflation may be more prolonged than many are expecting. Due to the heavy weight given to shelter, housing could contribute more than 2 percentage points to core CPI inflation by the end of 2022 and about 1 percentage point to the core PCE. Both would be the strongest contributions since 1990.

Higher Inflation Has Yet to Include House Price Surge

The April jump in the annual CPI reading to 4.2 percent caught many observers by surprise. However, based on the muted financial market response, most participants appeared to interpret the jump as largely transitory.

The bulk of the 0.8 percent monthly rise was driven by factors expected to be temporary related to the reopening of various service industries and supply chain issues in auto manufacturing. While these components are likely to drive stronger inflation through at least June, we expect that the pace will wane later this year. However, pressure is building within the largest component of the index – shelter – and it could replace current surging components as the major driver of measured inflation over the coming quarters.

Despite rapid house price gains over the past year, the housing components of the major inflation indices decelerated significantly from roughly a 3.5 percent annual pace pre-COVID to 2.0 percent in April 2021. The disconnect is due to the way inflation indices measure housing costs. Homes are considered long-lasting investment goods rather than consumption items. Therefore, inflation measures use an estimate of the cost of service that housing provides its occupant, referred to as shelter, as opposed to changes in the asset price. The cost of shelter is the sum of two components; the first is a measure of rents of primary residences (rent); the second is an estimate of the rent that owner-occupied housing could command called Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER). These measures tend to move together as the OER of a specific owner-occupied unit is estimated in part by observed actual rents on similar types of properties.

Following the initial COVID-19 outbreak, asking rents fell as the economy contracted. Later, many renters took advantage of low interest rates and the ability to work remotely to purchase homes, softening demand for rental units. However, as the labor market has improved and activities reopen, asking rents have begun to increase.

Rent Inflation Is "Sticky"

The CPI's measures of rent and OER meaningfully lag movements in home prices. Leases are typically set for a year, and even when a unit is up for renewal, landlords are either legally unable or are hesitant to raise rents as strongly on existing tenants. Given inflation indices capture current rents paid rather than vacant unit asking rents, the measures adjust slowly. On a year-over-year basis, house price gains historically lead changes in the CPI shelter cost measures by about 5 quarters. It has now been over a year since the COVID-19 outbreak. Leases signed in its wake when few landlords or tenants were likely expecting a coming surge in home prices and a strong economic recovery will now face upward rent adjustments going forward. This should soon influence annual inflation measures.

Rents are also more stable than house prices. The latter are measured via recent transactions rather than lagging lease rates. Additionally, just as equity share prices can deviate from underlying earnings trends, so too can the price of a home relative to the rent that the property could command. Changes in future expectations, long-run interest rates, and risk appetites can drive outsized swings in home prices. Speculation can become excessive when the price deviates significantly for too long from the underlying income stream, such as over the 2002-2007 period. At that time, real measures such as the supply of homes for sale and vacancy rates rose, in contrast to the current period of rapid home price appreciation in which the single-family vacancy rate and total homes available for sale have declined. The house price-to-rent relationship has therefore varied over time.

How Much Increase Is in Store?

For a better estimate of the shelter-driven inflation we expect is approaching, we built a simple linear regression model to help explain historical deviation between house prices and OER. Using quarterly data, the model is estimated from Q1 1984 (first full year of the OER series) through Q1 2020 (pre-COVID) and used to forecast thereafter. In it, the annual percent change in OER is a function of:

- Annual house price growth, as measured by the National Case-Shiller Index. The value five quarters prior is used to align with the previously discussed timing lag observation.

- The single-family rental vacancy rate, as reported by the Census, which captures single-family rental market tightness. The average of the past year is used to minimize noise as well as to pick up conditions corresponding to the prior year's lease signings. Additionally, a multiplicative "interaction term" with the house price variable is added. Together, these seek to differentiate the effect of house price growth on rents due to underlying scarcity of units versus speculative activity.

- 1-year inflation expectations, as measured by the Cleveland Fed Index. The average of the third and fourth quarter lag is used, again reflecting the past year’s lease signings. We hypothesize inflation expectations are particularly important in determining rent increases due to leases being locked for a year. Landlords expecting higher inflation will list a higher rent, which tenants may be more willing to accept believing rent will go higher.1

The model explains about 85 percent of variation in annual OER growth2. The forecast utilizing current data suggests that OER will soon accelerate3. By mid-2022 it projects annual growth near 4.5 percent. However, the oddities of the COVID-19 shock may affect the timing and magnitudes. House price growth may have been pulled forward and rents will take longer to catch up. Alternatively, when past predictions missed to the downside, as had occurred in the most recent quarters, an overshoot often followed, suggesting a faster catch-up pace could occur.

Regardless, strong house price appreciation is expected in the near term and rising overall inflation should push up future expectations. If we assume that 1) seasonally adjusted house prices continue to increase through the end of 2021 at the same pace that occurred over the past three months, and 2) inflation expectations trend higher toward a level comparable to the highs of the mid-2000s and late 1990s, the model output predicts annual OER growth of 5.7 percent by the end of 2022. If realized, this would be the strongest rate since 1990. There is, of course, uncertainty around this prediction, but it is likely that shelter-driven inflation will accelerate considerably.

Bottom Line for Overall Inflation

While shelter inflation is the combination of actual rents and OER, for this exercise we assume OER is a reasonable proxy of total shelter cost. About three fourths of shelter CPI is made of OER while roughly half of the rent component is attributed to single-family rents. Thus, OER inflation is likely representative of a large majority of shelter inflation. While the portion representative of multifamily rents may be softer going forward, apartment building price indices did not show meaningful slowdowns this past year and asking rents are expected to be at least in line with inflation aside from a few large metro urban cores. National rent indices report a bottoming in Q4 2020, with some timely measures showing rapid increases in the current quarter. Therefore, we believe deviation is likely to be modest.

The effect is less pronounced for the PCE deflator, as it assigns a lower weight to shelter. This is primarily due to it measuring a wider basket of items than the CPI. The CPI records prices of goods and services paid for out of pocket, while the PCE has a broader definition of consumption, which includes items paid for indirectly or through a third party, health insurance premiums being a major example. By the end of 2022, in the continued house price growth scenario, a full percentage point would be contributed to the core PCE, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation gauge.

Given the Fed's long-run 2.0 percent target for core PCE inflation, there is little room for price growth among the items composing the other 82 percent of the basket. Inflation in 2022 could be well above the Fed’s target even if other transitory effects wane. If inflationary expectations move up more aggressively then we assumed or house prices fail to decelerate in 2022, inflationary pressure would be even stronger and could persist well into 2023 or 2024. Therefore, we see upside risk to inflation from housing-related dynamics as a key concern, and it may ultimately play a large part in driving the Fed’s eventual policy tightening.

Eric Brescia, Economist

Economic & Strategic Research (ESR) Group

June 08, 2021

The author thanks Ricky Goyette and Rebecca Meeker for their contributions to this edition of Housing Insights as well as Kim Betancourt, Doug Duncan, and Mark Palim for their valuable comments. Of course, all errors and omissions remain the responsibility of the author.

Data sources for charts: Bureau of Labor Statistics, ApartmentList.com, RealPage, Census Bureau, S&P Case-Shiller, Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis

1 We also considered variables accounting for the long-run decline in both nominal and real interest rates over the past 40 years. All else equal, lower rates likely influence the price-to-rent ratio. Landlords will require a lower rate of return as fewer higher-yielding investment alternatives are available, while tenants weigh the price of rent versus the cost of a mortgage payment. However, we find due to the model specification of annual rates of change, effects from this long-run drift are mostly removed.

2 See Appendix A for regression results.

3 We estimate home price growth for Q2 2021 using partially available data and more timely proxy measures. This allows for a forecast through Q2 2022. We assume that inflationary expectations and vacancy rates remain constant at the most recent values.

Opinions, analyses, estimates, forecasts and other views of Fannie Mae's Economic & Strategic Research (ESR) Group included in these materials should not be construed as indicating Fannie Mae's business prospects or expected results, are based on a number of assumptions, and are subject to change without notice. How this information affects Fannie Mae will depend on many factors. Although the ESR group bases its opinions, analyses, estimates, forecasts and other views on information it considers reliable, it does not guarantee that the information provided in these materials is accurate, current or suitable for any particular purpose. Changes in the assumptions or the information underlying these views, including assumptions about the duration and magnitude of shutdowns and social distancing, could produce materially different results. The analyses, opinions, estimates, forecasts and other views published by the ESR group represent the views of that group as of the date indicated and do not necessarily represent the views of Fannie Mae or its management.